Commercial diving didn’t start with training programmes or safety standards. It started because there were jobs underwater that someone needed to do.

Before certifications, manuals, cameras, or comms, people went down because that was the work available to them. Simple as that.

A lot of what we now call “best practice” came much later.

Before Equipment, There Was Necessity

Japanese ama divers. Image courtesy of Kumi Kato.

Long before diving was formalised, people were diving for a living.

In parts of the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Asia, breath-hold divers harvested pearls, sponges, and food. One breath at a time. No gauges, no backup air, no real margin for error.

They didn’t do it for exploration or curiosity. They did it because it fed their families.

That was commercial diving in its earliest form. Go down, bring something back, repeat.

The Diving Bell: Staying Under a Bit Longer

18th century engraving of Halley's diving bell

©Museum of the History of Science, University of Oxford.

By the 1500s, people started experimenting with ways to stay underwater longer. The diving bell was one of the first workable ideas. Trap air in a chamber, lower it down, and use it as a place to breathe before heading back out.

It wasn’t comfortable or particularly safe, but it worked well enough to change how people thought about underwater work.

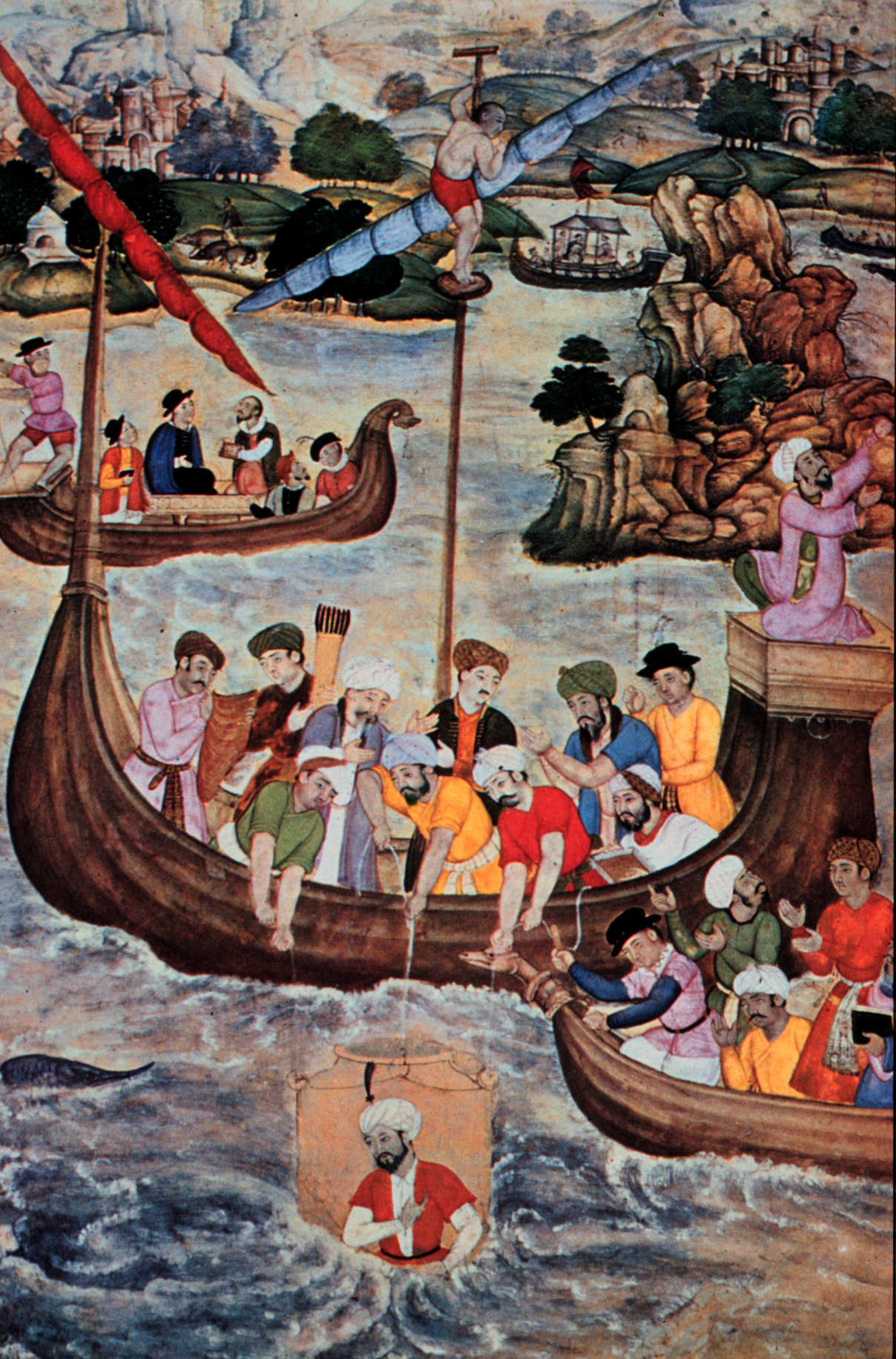

16th century Islamic painting of Alexander the Great lowered in a glass diving bell

Instead of short visits, divers could now spend time below. Enough time to actually build, recover, and repair things.

The Hard-Hat Era and the Cost of Progress

The 1800s is when commercial diving began to resemble the job we recognise today.

With surface-supplied air, sealed suits, weighted boots, and copper helmets, companies such as Siebe Gorman enabled underwater construction, salvage, and ship work on a scale that hadn’t been possible before.

Two divers, one wearing a 1 atmosphere diving suit and the other standard diving dress, preparing to explore the wreck of the RMS Lusitania, 1935

What they didn’t understand yet was decompression.

Divers were getting injured. Some were paralysed. Some didn’t make it back. The risks were real, and the knowledge wasn’t there yet.

A lot of what we now take for granted was learned the hard way.

When Science Finally Caught Up

Experimental diving equipment on a pier in Fort Pierce, FL in 1944. This gear appears to have been made from modified mine rescue equipment. Image: Naval History and Heritage Command 80-G-264541

As diving became critical to military and industrial work, especially during wartime, it became clear that guesswork wasn’t enough.

Organisations like the United States Navy began serious research into decompression, gas behaviour, and dive planning. Slowly, diving moved from trial-and-error toward something more structured.

Every table, limit, and rule used today exists because earlier divers didn’t have them.

Going Deeper, Working Longer

Scuba changed recreational diving, but commercial work largely stayed surface-supplied. When the job involves heavy tools, poor visibility, and real consequences, reliability matters more than convenience.

A US Navy crewman exits the submarine’s escape hatch wearing the "Momsen Lung" emergency escape breathing device during the submarine’s sea trials in July, 1930. The emergency breathing device was named for its inventor, U.S. Navy submarine rescue pioneer Cdr. Charles "Swede" Momsen.

Mixed gases like heliox allowed divers to work deeper and stay clearer-headed. Offshore oil and gas expanded rapidly, and with it came longer dives, tougher conditions, and more demanding schedules.

This wasn’t adventure diving. It was labour, carried out underwater.

Saturation Diving: Living the Job

By the 1960s, saturation diving pushed things even further.

Instead of decompressing after every dive, divers stayed under pressure for weeks at a time. They lived in chambers, went to work from them, and decompressed once at the end.

A vintage photo of two divers in a decompression chamber.

It worked, but it required discipline, routine, and trust in the system. Mistakes had consequences that followed you for days, not minutes.

Today’s Reality

Modern commercial divers have better equipment, clearer communications, and stronger safety standards. Training is more thorough. Fatalities are lower.

But the work itself hasn’t become easy.

The Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and Maritime Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) conducting enforcement checks at Singapore anchorages. (Photo: MOM)

Steel is still heavy. Visibility still disappears. The ocean still behaves the way it always has.

No matter the job, the goal is unchanged. Go down, do the work properly, and come back.

Why This Still Matters![]()

Commercial diving isn’t a trend or an image. It’s a job built over generations by people who accepted real risk because the work needed doing.

At Sons of Triton, that history isn’t something we reference for branding. It’s something we take seriously. The decisions we make come from understanding what this work actually involves.

Because none of this was handed down neatly. It was built slowly, dive by dive.